CN / EN

CN / EN

IROS 2025 | Tianjin Univ Neck Support Exoskeleton - CHINGMU Motion Capture

Research on Neck Support Exoskeletons

In occupations requiring prolonged forward head posture, such as surgeons performing operations or assembly line workers, staff often need to maintain a forward-flexed head and neck position. The weight of the head places a significant load on the neck muscles and spine, leading to a substantially higher probability of neck-related disorders among these workers compared to the general population. However, there is a notable lack of ergonomic solutions that can provide head support assistance, effectively reduce the burden on neck muscles, and not interfere with normal operational functions in various environments.

Based on this, a research team from Tianjin University has conducted related research and designed a novel variable stiffness cervical exoskeleton using a pneumatically driven tensile actuator. This cervical support exoskeleton allows head movement with minimal resistance in its flexible state, ensuring the wearer's head movement flexibility and smoothness during work. In its rigid state, it can provide support assistance for the head, effectively alleviating the burden on neck muscles. This research has been accepted for publication at IROS 2025, a renowned conference in the field of robotics.

I. Research Solution

The research team designed and fabricated a variable stiffness cervical exoskeleton weighing only 520g. By incorporating a variable stiffness actuator, this semi-active exoskeleton achieves a lighter weight and better wear comfort.

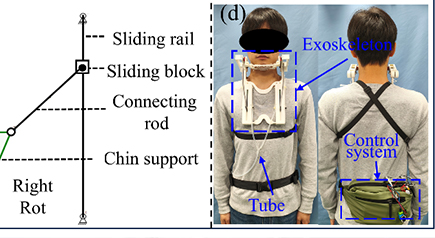

The cervical exoskeleton has two main degrees of freedom: flexion in the sagittal plane and axial rotation. The flexion degree of freedom in the sagittal plane is influenced by the stiffness of the variable stiffness actuator. When the variable stiffness actuator is in the flexible state and the head flexes forward in the sagittal plane, the L-shaped support rod passively rotates and acts on the variable stiffness actuator, which can then elongate with minimal resistance, ensuring the exoskeleton does not significantly hinder normal movement. After the variable stiffness actuator switches to the rigid state, its resistance to elongation increases significantly. The head's weight acts on the variable stiffness actuator through the chin support and the L-shaped support rod, allowing the neck extensor muscles to relax, and the exoskeleton provides stable support for the head. Axial head rotation is achieved through a guide rail linkage mechanism. This mechanism includes a slide rail, slider, linkage, and chin support. When the head rotates, the movement is transmitted to the slider via the linkage, and the slider slides along the guide rail to accommodate the head movement. Furthermore, during head flexion, the chin retracts towards the neck. This mechanism not only enables unobstructed head rotation but also compensates for chin retraction, maintaining continuous contact with the chin support, thus ensuring free head rotation without compromising the support function.

Figure 1: Specific structure of the cervical support exoskeleton

Based on the above structural design, the research team recruited subjects to conduct wear tests of the exoskeleton system, evaluating its impact on the range of motion (ROM) of the cervical spine and its assistive support performance.

Solution Innovations and Advantages:

The exoskeleton integrates a variable stiffness actuator, enabling active stiffness adjustment to reduce resistance to normal user movement and provide appropriate support.

The exoskeleton design considers human physiological characteristics, decoupling head flexion and rotational movements, ensuring support function without restricting head rotation.

The exoskeleton weighs only 520g (excluding the waist-worn control system), making it lighter than most existing neck exoskeletons.

II. Experimental Verification

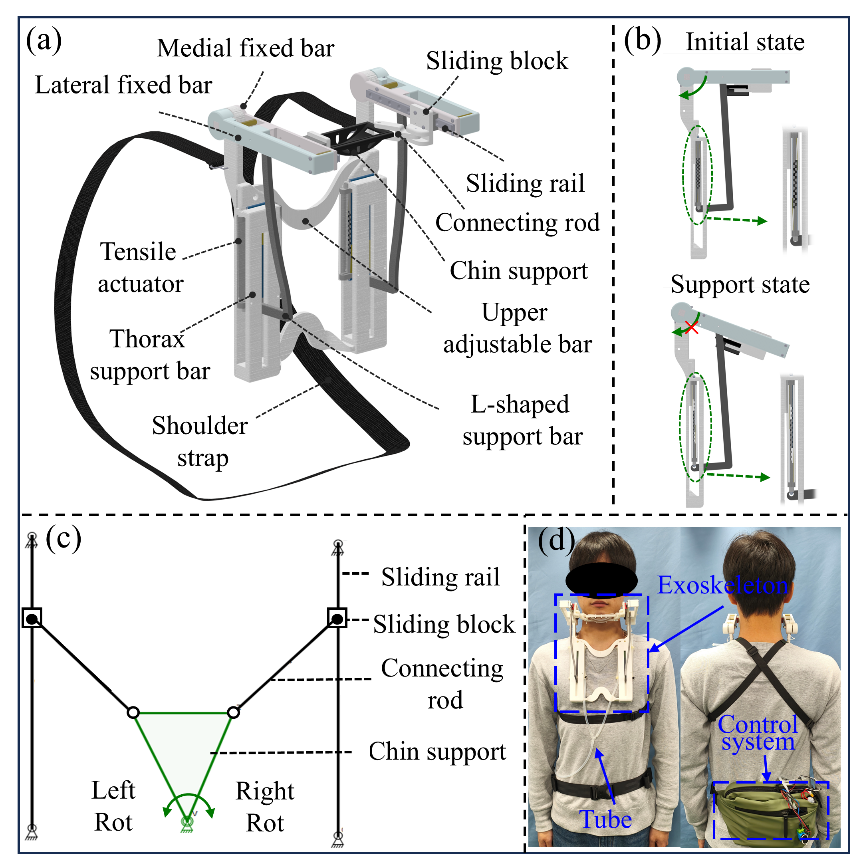

Motion information was captured using an optical motion capture system developed by CHINGMU (Shanghai Chingmu Visual Technology Co., Ltd.). This system was equipped with 4 high-speed optical cameras (MC4000), recording head movement information at a sampling frequency of 110 Hz. The motion capture system is shown in Figure 2(a). As shown in Figure 2(b), 9 markers were placed on the subject's torso and head. The high-speed cameras captured the time-varying position information of the markers, which was then exported by the acquisition software as position change data. The range of head motion was subsequently calculated.

Figure 2: Optical motion capture experimental setup

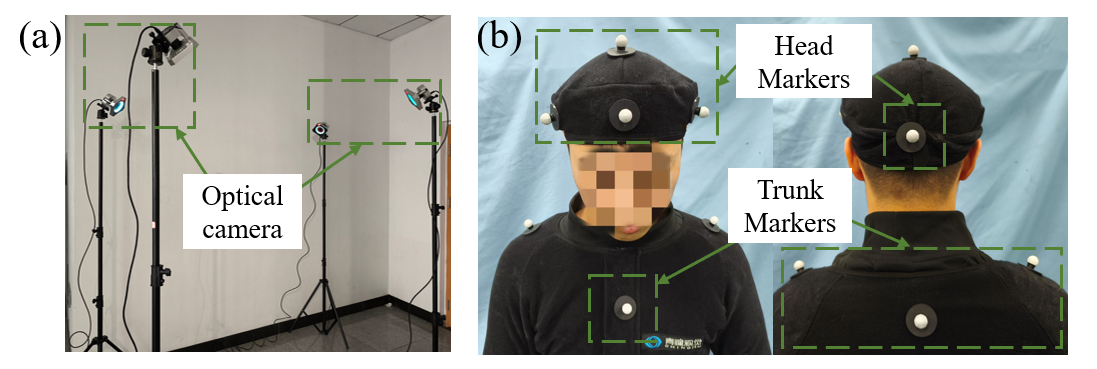

This study recruited 5 subjects (Age: 25.6 ± 1.4 years, Height: 180.4 ± 4.3 cm, Weight: 70.1 ± 7.9 kg). Each subject was required to perform the three motion tasks shown in Figure 3 at a self-selected comfortable speed, under two conditions: wearing the exoskeleton (in flexible state) and not wearing the exoskeleton. Each task was repeated 5 times, and the average range of motion over the 5 trials was calculated.

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of the three motion tasks: Sagittal plane flexion and axial rotation.

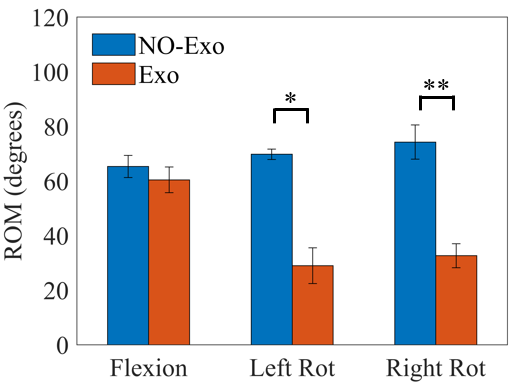

A comparison of the average joint range of motion for the 5 subjects before and after wearing the exoskeleton is shown in Figure 4. The length of the colored bars represents the average range of motion of the five subjects, and the error bars represent their standard deviation. To analyze whether the results were statistically significant, a paired sample T-test was performed on the range of motion results. In the figure, * indicates p < 0.05, and ** indicates p < 0.01.

Figure 4: Comparison of the average range of motion for each movement across the 5 subjects

The experimental results showed that when wearing the exoskeleton, the average ranges of motion for the 5 subjects were 60.4° ± 4.7° for head flexion, 28.9° ± 6.5° for left rotation, and 32.6° ± 4.4° for right rotation. Compared to the state without the exoskeleton, the ranges of motion for head flexion, left rotation, and right rotation decreased by 7.51 ± 6.2%, 58.51 ± 8.4%, and 56.07 ± 5.0%, respectively. The study indicates that the head flexion range of motion can meet the practical needs of surgeons during operations. Although the range of motion for left and right axial rotation decreased significantly, most activities only require 20% to 40% of the total cervical range of motion, which the proposed neck exoskeleton in this study can fully satisfy.

III. Experimental Outcomes

This study demonstrates that this variable stiffness cervical exoskeleton can provide the intended support for forward head flexion without significantly restricting normal head movement. It can reduce the physical burden on neck muscles, and its light weight and minimal restriction on head movement meet the needs of long-term forward head posture tasks in scenarios such as surgical operations. It provides an effective approach to addressing neck health issues for relevant occupational groups.

References:

E Tetteh, M S Hallbeck, G A Mirka, “Effects of passive exoskeleton support on EMG measures of the neck, shoulder and trunk muscles while holding simulated surgical postures and performing a simulated surgical procedure,” Appl Ergon, vol. 100, Apr. 2022.

G P Y Szeto, P Ho, A C W Ting, et al, “Work-related musculoskeletal symptoms in surgeons,” J. Occup. Rehabil, vol. 19, pp. 175-184, Apr. 2009.

I Dianat, A Bazazan, M A S Azad, et al, “Work-related physical, psychosocial and individual factors associated with musculoskeletal symptoms among surgeons: Implications for ergonomic interventions,” Appl Ergon, vol. 67, pp. 115-124, Feb. 2018.

T A Plerhoples, T Hernandez-Boussard, S M Wren, “The aching surgeon: a survey of physical discomfort and symptoms following open, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery,” J. Robot. Surg, vol. 6, pp. 65-72, Dec. 2012.

M Wohlauer, D M Coleman, M Sheahan, et al, “SS12. I feel your pain—a day in the life of a vascular surgeon: results of a national survey,” J. Vasc. Surg, vol. 69, Jun. 2019.

P Gorce, J Jacquier-Bret, “Effect of assisted surgery on work-related musculoskeletal disorder prevalence by body area among surgeons: systematic review and meta-analysis,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol .20, Jul. 2023.

E Nutz, J S Jarvers, J Theopold, et al, “Effect of an upper body exoskeleton for surgeons on postoperative neck, back and shoulder complaints,” J Occup Health Psychol, vol. 66, Apr. 2024.

A M Geers, E C Prinsen, D J Van Der Pijl, et al, “Head support in wheelchairs (scoping review): state-of-the-art and beyond,” Disabil. rehabilitation. Assist. Technol, vol. 18, pp. 564-587, May. 2023.

A S A Doss, P K Lingampally, G M T Nguyen, et al, “A comprehensive review of wearable assistive robotic devices used for head and neck rehabilitation,” Results Eng, vol. 19, Sep. 2023.

C A Yee, H Kazerooni, “Reducing occupational neck pain with a passive neck orthosis,” IEEE T-ACES, vol. 13, pp. 403-406, Nov. 2015.

C Zhang, J M Hijmans, C Greve, et al, “A novel passive neck and trunk exoskeleton for surgeons: design and validation,” J. Bionic Eng, pp. 1-12, Dec. 2024.

H Zhang, K Albee, S K Agrawal, “A spring-loaded compliant neck brace with adjustable supports,” Mech Mach Theory, vol. 125, pp. 34-44, Jul 2018.

S P Torrendell, H Kadone, M Hassan, et al, “A neck orthosis with multi-directional variable stiffness for persons with dropped head syndrome,” IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett, vol. 9, pp. 6224-6231, Jul 2024.

B C Chang, H Zhang, S Long, et al, “A novel neck brace to characterize neck mobility impairments following neck dissection in head and neck cancer patients,” Wearable Technologies, vol. 2, Jul. 2021

L Yang, T Wang, T K Weidner, et al, “Intraoperative musculoskeletal discomfort and risk for surgeons during open and laparoscopic surgery,” Surg Endosc, vol. 35, pp. 6335-6343, Nov. 2021.

D G Cobian, N S Daehn, P A Anderson, et al, “Active cervical and lumbar range of motion during performance of activities of daily living in healthy young adults,” Spine, vol. 38, pp. 1754-1763, Sep. 2013.

H Yajima, R Nobe, M Takayama, et al, “The mode of activity of cervical extensors and flexors in healthy adults: A cross-sectional study,” Medicina, vol. 58, May. 2022.

M N Mahmood, A Tabasi, I Kingma, et al, “A novel passive neck orthosis for patients with degenerative muscle diseases: development & evaluation,” J Electromyogr Kinesiol, vol. 57, Apr. 2021.

E A Keshner, D Campbell, R T Katz, et al, “Neck muscle activation patterns in humans during isometric head stabilization,” Exp Brain Rese, vol. 75, pp. 335-344, Apr. 1989.

H Zhang, S K Agrawal, “Kinematic design of a dynamic brace for measurement of head/neck motion,” IEEE Rob. Autom. Let, vol. 2, pp. 1428-1435, Jul 2017.